TRANSPLANTED from Europe to Phoenix over 45 years ago, Poet David Chorlton was immediately captivated by the desert, but he did not create poems about it for years.

“To a European the desert is a new experience. It took me more than a decade to learn about what lives and grows here and to absorb the nature of a spare, dry country that produces its own tension and the beauty of life that wastes nothing.”

Many of his poems are steeped in desert scenes and wildlife, reflecting both a reverence and connection to the natural world. His poems often begin as small observations that build into larger understandings. “My poems progress by trying to create an aesthetic out of the observations. I think of the process as akin to dreaming, when a dream gathers whatever is on my mind and arranges it to fit its own needs.”

David spends a great deal of time observing and writing. “I lead a quiet life. Writing is one thing that illuminates it and, more importantly, it adds to my sense of what is around me. Writing helps me find words to better understand what goes on out of reach. Language doesn’t think for us, but it does sharpen and clarify our thoughts.” Dreams and the subconscious play a big part in the creation of his poems. “I have long equated poetry with dreaming, and credit my subconscious with my best writing moments.”

For many years he and his wife lived in the Willo district of Phoenix, then moved to Ahwatukee in the southeastern corner of the metro area about ten years ago. After 44 years of marriage, he was widowed in 2020. He is now surrounded by his dog, two adopted cats and three rescued birds. “Once the creature chores are done, I can get back into my mind to see whether there is anything worth excavating.” Poetry is both his art and a way to stay grounded. “I suppose I could easily have become a cranky individual who talks to himself during daily walks. Writing poetry is more socially acceptable!”

David is a prolific writer, publishing over 40 poetry collections and chapbooks from small presses. His latest book is Desert of Earthly Delights from Cholla Needles in Joshua Tree, California. Sharing his work through books and readings is an important aspect of his art. “I hope whatever I write goes where it will be read, so it becomes a communication with strangers if all goes well.” He enjoys reading at local venues like Changing Hands and Esso Coffee House. “Writing is often the art of an introvert, while presenting the final work calls for more of an extrovert. The least I expect, even from myself, is to read as though the poem matters.”

Although David is also a talented photographer and painter, it is only recently that he has paired paintings with poems. “A traditional approach to painting landscape or nature is to depict a specific scene, but painting nature doesn’t have to mean painting what is seen. On occasion I translate nature into a kind of watercolor abstraction. The colors flow as the work takes form and the medium has a life of its own. So, a painting and a poem often develop side-by-side as they address nature.”

The following combination of poem and painting, “Sun Rising,” is a lovely example of the poet collecting images and allowing them to subtly expand into deeper themes. “I have a great view of the sunrise on South Mountain each morning. The painting lives from its textures, while the poem associates what I see with that dream self. I am reassured that my immediate surroundings can stimulate creativity.”

Our current climate crisis is never far from David’s thoughts. “There has been a lot of poetry written and published that adds to the shared understanding of why we should be concerned. The accumulated effect of many voices is beneficial even if there are no statistics to measure it by. Poetry can sidestep scientific complexity and be both profound and simple at once. Given the chance to communicate, poetry really can be the individual voice that shines a light on collective concerns.”

More at davidchorlton.mysite.com.

Sun Rising

Slow light on the awakening road, a thrasher

calling up the sun, the sky breathes in, breathes

out, a dream floats away

without knowing how it ends. Desert red,

a world apart. No interest rates, no headlines, just

a jackrabbit who listens

to the stones whispering. It’s too early

for suffering to begin

or souls to rise

in protest. It’s beautiful to see

the ancient sun the people here before

worshipped as it rose

and whit-whit now the mountain

holds its heart up for all the world to see.

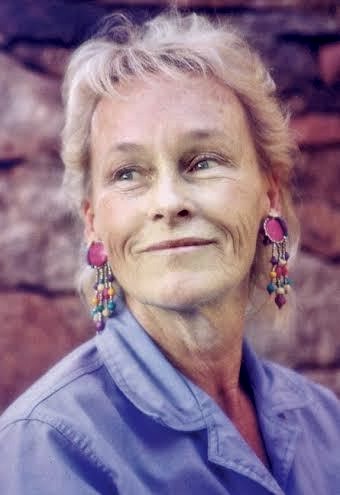

ARRIVING in Prescott more than four decades ago, poet Susan Lang reshaped the town’s creative landscape, designing and implementing two innovative programs that welcomed famed writers and presented opportunities for students and residents to interact with and learn from these masterful authors.

The road wasn’t easy. Susan was teaching writing at Yavapai College, at the time a small community college geared toward vocational training and core classes, not the lofty creative enterprises Susan envisioned. Through trial and error she learned to submit grants and to convince her supervisors of their value. In collaboration with Prescott College she was eventually able to establish the Southwest Writers Series in 1985. She directed that program for over 20 years, bringing in dozens of leading writers to read and speak. “These were all the writers I loved, too many to mention: Grace Paley, Carolyn Forche, Marge Piercy, Tim O’Brien, Galway Kinnell, Sharon Olds, John Nichols . . ..” Many of the writers became close friends with Susan over time, returning often. Looking back, Susan is still amazed by the project’s impact on the community and herself. “The program came from the center of my being. I got to do things I never dreamed I could.”

In 1996 Susan also launched the Hassayampa Institute for Creative Writing, an annual conference offering workshops, readings and lectures by many of the same talented writers. “It was the perfect opportunity for people to get to know them, learn from them, share with them. It put our small town on the literary map. We were nationally and internationally known.” Although the program was very popular, the college withdrew support and it closed after twelve years. Despite the difficulties getting these programs going, Susan feels she was always on the right path. “When you’re doing what you’re meant to do against odds, it seems to generate synchronistic experiences or incidents that light your path in the right direction.”

During those years Susan worked on her own writing. Among other works of fiction she published a trilogy about a woman homesteading in the southwestern wilderness in the years leading up to World War II. She recently published a memoir, Running Barefoot, that details her fascinating life, including growing up on a homestead, communal living, teaching on the Navajo reservation, and talking her way into college without the benefit of a high-school education. She also managed to raise seven children, often as a single parent. Susan’s fiction is populated with brave and feisty women much like herself.

At heart, though, Susan considers herself a poet. “I found myself in poetry. Poetry opened me up.” She has had many poems published in renowned journals, including Idaho Review, Red Rock Review, Iris, and The Raven Review. She believes poetry is a search for meaning that will disclose itself if allowed. “In poetry, different things connect. A synchronicity reveals itself. I can be walking in the forest and stumble on an idea. Out of nowhere something unexpected comes to me that has resonance, that belongs in the poem.” She feels that staying open to these events permits poems to discover/uncover their purpose. “It’s hard to talk about what can’t be said. And that’s what poetry’s about — it gets to the heart of every experience.”

In discussing the following poem, Susan details several incidents where a kind of synchronicity influenced her writing. The Leonid meteor shower is an annual event that takes place on November 17, and on that date Susan started in her current position as event coordinator for the Peregrine Book Company. Her fascination with physics creates an underlying connection between science, stars,and human existence, and while writing the poem, she was reading Stephen Hawking’s book. She attended a conference in Aspen where, unknown to her, he was the keynote speaker at another nearby conference. While there she turned a corner, tripped on his wheelchair and accidentally fell in his lap. These diverse and comical factors combine to create a poem that succeeds on a profound level.

A little synchronicity helped Susan though her early days in Prescott, and continues to influence her work in positive ways. She is still writing and sharing her poetry at open mics in town. She will be the featured poet at Peregrine Book Company in February. Much has changed over the years, but Susan’s imaginative efforts are still felt and appreciated throughout the community.

Contact Susan at susan@peregrinebookcompany.com.

Waiting for the Leonids

(Flagstaff, November 17, 1998)

For Stephen Hawking

Star after star punctuates the darkness

as the cosmic question mark rises above the horizon,

inverted,

as if it were its own question and not ours. Higher

and higher Leo floats into sight,

and we wait on this cold earth night for illumination

to shatter the sky, to remind

us why we are here warping time and space with our gravity:

mere densities of matter born of some quantum fluctuation

who look back with Heisenberg eyes and fall in love

with the self we imagine we were

before time mattered

inflated and radiated into space

finite and without boundary,

crammed as we were into the same particle.

What strange energy formations we earthlings are:

thermodynamic bodies separate unto ourselves,

each mind a singularity, radiating consciousness

back into the universe. Are we but the thoughts

of stars? Surely they would have finer thoughts. Are we

their suffering, their laughter, their joy?

For our being is but an extension of their being,

Tonight, a few meteors flash and fade above,

fleeting events in a field of possibility,

as are we.

SOMETIMES it’s a long journey back to our beginnings. Poet Dominique Ahkong recalls swimming with her mother in the ocean in Mauritius, the island her parents are from. “When I was a child we’d often swim together, but when the water was too cold for me I’d wrap myself in a towel and watch her from the shore.”

Many years later, after a long period of caring for her mother during chemotherapy, she’d return to the image of her mother swimming and incorporate it into a poem, “Ghazal for Familiar Women.” “I wrote it in the guestroom of my inlaws’ basement in Southern Colorado. I’d been returning to a memory of standing at the hospital pharmacy, waiting to receive my mother’s medication, and noticing women around me who from the back resembled my mother. I knew they were cancer patients partly because of the way they dressed, but it was mainly the appearance of their upper bodies that struck me as familiar.”

A ghazal (pronounced 'gazahl') is an Arabic poetic form made popular by medieval Persian poets. It characteristically consists of complete couplets and an intricate rhyme scheme. Each couplet ends on the same word or phrase (the radif) and is preceded by a rhyming word (the qafia). The last couplet includes a proper name, often the poet’s. Although not quite a true ghazal, Dominique employs many of the distinguishing elements of the form to create a poem whose repetitions capture a haunting sense of regret. “The poem came together very quickly, one week. Five months later, it found a home.” It was also nominated for Best New Poets Anthology.

Dominique is of Hakka-Mauritian descent. She was born in the UK and raised in Singapore. “Like many writers, I was a shy child and an avid reader. I was very much drawn to language, music, and creative expression.” She eventually attended school in the US, majoring in women and gender studies, then focusing on film and visual media. Her love of writing was never far from her mind. “Still poetry found me. One of my favorite classes in my graduate school program was called 2x2 (Creating media for tiny screens). My instructor asked us to create a video or animation set to a poem. I animated Li-Young Lee’s Early in the Morning. I didn’t realize the impact that reading the poem out loud over and over again would have on me. As part of my thesis, I also ended up making a popup book with little poems hidden in pieces of paper furniture.”

Over time, she would make her way back to poetry. “I wrote here and there, got my first poem published at 31. I didn’t establish a real poetry practice until I was 39, during Covid, when I moved to Arizona. My second poem was published exactly ten years after my first. I’m now 43 and have had 21 more poems published in journals, but I’m still writing towards my first collection! A different path for every poet.”

Dominique now resides near Chino Valley with her husband, poet Johnny Cordova. Together they co-edit and publish the renowned Shō Poetry Journal. “Publishing is very time-consuming because I wear many hats, and because the journal is still a toddler, so to speak.” But she also finds it gratifying. “It is a responsibility and a gift. It’s brought me into community with other poets and has been incredibly enriching and expansive for my own poetry practice. I learn from the journals that have supported my own work and I learn from other poets.” Editing has taught her a lot about publishing. “I’m now aware that there’s so much that goes unseen, so I’m more patient and try not to take rejections personally.”

Returning to “Ghazal for Familiar Women,” Dominique explains, “It’s possible to read this poem and say there is little nuance in the speaker’s views on faith — perhaps until the final couplet. I also employed a call to the poet’s proper name that traditionally appears in a ghazal’s last lines. My name, Dominique, means “of the Lord, close to God,” which has always given me pause. But underpinning the ghazal is this sense of longing, an ache, which is expressed through the repetition of the radif: back / back / back. I think that borrowing the rough form of a ghazal helped birth a longing for my own trust in the divine, a way to meet my mother in her faith through a vehicle that is true for me.”

More at dominiqueahkong.com and shopoetryjournal.com.

Ghazal for Familiar Women

In the way we can spot kinfolk from the back

by their gait, these women unknown to me, backs

facing me, feel related. More than the long sleeves

and bucket hats, it’s the eroded downstroke of their backs

that’s vernacular, it’s what they do not do, even while

their eyes are watching God disrobe and back

away. They hold out their veins, unblinking, while black

bags are hung from their necks like ropes. Back-

aches persist but do not fracture their language in this way.

Comfort is a drained infusion pump, three days a foe. Back

at home, as night falls, a husband holds his wife’s hand.

His daughters will rub their mother’s unrobed back

and cover it after her body’s churning. Her

requested balm: atonal invocations back to back.

Will you embody your name, Dominique? See your mother

plunge into the cold ocean, then turn to float on her back.

First published in Sugar House Review Issue 27, Winter 2023

For Tempe poet RS Mengert, poems are a viaduct to the past, a re-envisioning of half-remembered events that still hold great sway. Many of his poems visit and revisit childhood experiences and memories to better comprehend their meaning. “It’s a long way from a nostalgic view of childhood, which for me always seems mostly like a place of fear, danger, ambivalence, with a few brilliant pockets of warmth and brightness. The speaker returns to the origins of his haunting, in which he still feels somewhat trapped.”

Reading Rob’s work is a like remembering the fear of the closet in a dark childhood bedroom. He describes “an absent father figure so mysterious and menacing that he appears almost as a boogeyman, a specter that haunts nightmares and anxious ruinations of insomnia. My mother was caught in the trenches with us, lost and confused, like the child she was trying so desperately to protect.” And those pockets of brightness? His grandparents. “In my poems they appear, often cryptically, as almost shamanic figures, priests, spirit guides, strega as my Italian ancestors might say, and the speaker is left to sort out the haunting in their absence, looking to their memory for guidance.”

Rob has been writing for a long time, but didn’t share his work with others till after he graduated from college. “I continued to write and take workshops to develop my craft, in night classes at ASU and Phoenix College. I had some good teachers in that period who prepared me to eventually attend the MFA program at Syracuse University. All the faculty at Syracuse — Mary Karr, Brooks Haxton, Chris Kennedy, Bruce Smith — were brilliant, and working with them was a life-changing experience. In particular, the late Michael Burkard was my thesis adviser, and he had perhaps the most profound influence on me. He opened me up to creative possibilities that I hadn’t experienced before, and he taught me how to trust my voice and my ear.”

Rob has appeared in many journals, magazines, and anthologies. He has won The Joyce Carol Oates Award for Poetry. His first full-length collection, Hereditary Casino, is coming from Moon Tide Press.

After a stint in Arizona in the early 2000s Rob left and returned for good in 2012 with his wife. “Having originated in Boston, growing up in the LA area and then coming of age in Las Vegas, I’m not sure I’ve ever really felt 100% at home anywhere. Alienation and feeling like a stranger in my own skin are recurring themes in my poems.” In spite of himself he has grown used to living in AZ. “It feels as much like home as anyplace likely will. Other than the heat (seriously, the only place I’ve ever been that’s hotter than Las Vegas), the sprawl and (often) the politics, I can honestly say I like it here.”

Rob has taught creative writing at local colleges. He now works in a public library. “I feel valued and appreciated there, along with a strong sense of accomplishment in the work we do. It makes me feel invested in the community in which I live. And the poetry community here, while small for an area the size of greater Phoenix, is welcoming and earnest without being cliquish. I don’t see us leaving anytime soon.”

The following poem is a profound glimpse into the anxieties and fears of a boy who cannot escape the problems that perennially await him at home. The writer describes the poem as autobiographical “more or less (I am a poet, not a memoirist).” The poet mixes spiritual and existential themes, all seen through the eyes of a child. One is imersed in vivid imagery and symbols: bogs, forbidden fruit, city soot, the unknown wild. The poet describes the child as “an old soul already living on high alert in an environment that is always potentially hazardous.” The “you” in the poem is his grandfather, who “becomes both demiurge/serpent and priest/redeemer.” Rob’s gift for capturing the sound and rhythm of language carry the reader through the poem. He adds, “So much beautiful imagery to work with, but it remains mysterious to me, and sometimes even frightening.”

Marshfield, Massachusetts

Its name was apt. Strewn with bogs

and marshes, fortresses of reeds and cattail,

smell of ocean always just below the heavy air.

You hid me from my father there

while mother plotted our escape out west.

A wooded coppice hedged your neighborhood,

dense with dappled foliage, gold and crimson blaze

that burned away the city’s soot

we carried with us. I was afraid

to venture there alone, but one day

you walked with me, took me by the hand, my Virgil

to that netherworld, and we grappled through the damp

mist-sprinkled thicket that smelled like firewood and God.

You grabbed a branch. You held it down

to show me a cluster of wild berries. I had been told

that wild berries were poison, that one should never touch

the strange, the unknown wild.

But you held the berries in your thick

North-ender’s hands as if they were as safe and ordinary

as the copper wire you had shown me in the basement.

The fruit was blue-black, each berry a tiny cluster

of egg-shaped cells, a honeycomb turned inside out

then smoothed around the edges.

You plucked some free, brushed them off,

and ate them. Not even washed.

Wild berries were poison, and

poison meant death. I had been told.

It was as though you had some secret gnosis,

and could eat God’s fruit unmediated,

and live.

You were immortal, I would die.

You held some out to me to share, but

I knew what I knew.

(Previously published in Italian Americana: Summer/Fall 2020)

Prescott Valley resident Tinamarie Cox first turned to poetry while journaling about her mental health. “When I began medication and talk therapy, I decided to dedicate more time to poetry, partially as a way to document my journey. I wanted to see my progress. I realized I didn’t have many names for what I felt. However, I had plenty of phrases, metaphors, and comparisons for the emotions I struggled to name. This is where taking up poetry, after a long hiatus, came into play. The therapeutic value of poetry allowed me to examine and explore what I was feeling.”

In that period she published her first book, Through a Sea Laced with Midnight Hues. She says, “As I began to take control of my mental health, I was journaling often and composing poems. Sifting through pieces to submit to publications, I saw the book’s theme appear. By becoming more self-aware and cataloging my emotions, I had unknowingly created the collection.”

Besides writing, Tina produces visual art. “Sometimes I just don’t have words. For those days I paint, mess around with digital images I’ve captured, or craft. Being creative is more of a need than a practice. Something needs to be expressed before I explode. Like taking the whistling kettle off the hot stove. Art projects allow me to feel and experiment in color. They give me a break from thinking.”

Her second poetry collection, A Numbers Game, will be published in March 2026. “Also sprouting from big emotions, this book juxtaposes my history with my present feelings. Heavily probing into my past, I concluded that creating art was just as important for my survival as writing. As the book grew, I selected pieces of art and personal photographs to include with the poetry, spanning from my childhood to my present self. I could look at my first collection as sort of an accident while A Numbers Game was very deliberate.”

Families past and present are great sources of inspiration for Tina’s poems. “My most vulnerable and impressionable years were spent with my family of origin. There are still many emotions from then that I continue to deal with, even as a more well-situated adult. I’ve been putting in the work to unlearn unhealthy patterns so that those dysfunctional cycles don’t get carried into my parenting. My children are my source of inspiration in just about everything. Seeing myself in their eyes motivates me to be a better parent (and human being in general) and to do the hard things past generations avoided. That means making my mental health and emotional wellbeing a priority, which in turn becomes a reason for writing.”

The following poems offer conflicting views on motherhood. “Mothers possess the ability to shape their children’s identities. The first poem focuses on the mother (or gardener) continuing toxic patterns, spreading the poison to the next generation. Mother/Gardener could grow a beautiful family of flowers, but instead, propagates weeds. The second poem is from the point of view of the adult child, realizing that change can (and needs to) begin with her. While the damage has already been done, she chooses not to do the same to her children. This Mother/Gardener understands that she can give her child the things she did not receive but always wanted: empathy, autonomy, individuality, acceptance, compassion, self-expression, understanding, patience, unconditional love, and equality. The greatest gift she can give her child is the ability to bloom into exactly who they were meant to be.”

Tina adds, “I never wrote these two poems intending to create interrelated pieces. But a lot of my earlier work, when put beside my newer pieces, would reflect the growth I experienced both emotionally and mentally over the years.”

Tina views poetry as an ever-changing medium. “Poetry serves many purposes. Through a poem, you can tell a story, recall a memory, make a wish, release your anger, contemplate your existence, vocalize for a cause, wonder about the future, or create something as inspiring as a piece of visual art. I never truly appreciated the versatility of words until I dove into writing poetry.”

More at tinamariethinkstoomuch.weebly.com.

The Gardener Grows Weeds

The seeds were planted into depths

of dark rotted earth,

in carefully measured rows, and watered daily

with the sweetest tasting venom, so

the roots would run deep

through an expanse of pure night,

the spindly veins invading,

amassing into a dense, tangled web.

And there would be no mistake

with what would take hold,

at what would grow,

strong and twisted,

depleting the soil of the garden bed.

Trained, thorned tendrils reached out,

curling fingers grabbing,

searching for a nearby throat.

The weeds crept further,

assailing and crowding out rivals,

each other,

spoiling tender membranes and

choking everything lush and green,

expanding as shadows.

Sour and poisonous botanicals cultivated and

harvested by their bitter queen,

the gardener

who painted her barbed roses black.

A Mother is a Gardener

I dreamed of you.

I dreamed for you.

And in the midst of my thriving garden,

I saw your young vines reaching for the sun;

stretching in all directions, away from me.

I feared and I ached

as the dreams I dreamt faded and crumbled;

as the colors I anticipated changed.

But rather than cut you down;

rather than trim and alter your growth,

I stepped aside to watch.

Something so much more beautiful than

my imaginings appeared, and flourished.

And then, I wished

with silent tears

that my gardener had waited and done the same

for me and my blooms.

My child, you are so lovely

without my shadows around you.

For Sedona poet Rex Carey Arrasmith, poetry is a way of both looking out and looking in. “Sometimes I find myself like a bird banging on the window at my reflection.” Poetry offers him opportunities to reevaluate experiences more deeply and from differing vantage points. “I am a pretty private person by nature, but when I write a poem it feels like I’ve been given permission to disclose far more than I would over, say, a beer with friends. It’s a way to connect with my own history — things I may have forgotten or my version of those things with a healthy dose of hindsight.”

After retiring from a long career at UnitedAirlines, Rex refused to slow down. “Being retired or older (gasp) means I have a lot more life experience to draw from. I’ve read more books; I’ve lived in more places. I also think it’s always good to have a plan for after retirement. Mine was to go back to school.” He received an MFA in fiction in 2018, following up with an MFA in poetry two years later. His writing has been featured in many literary journals and anthologies. He collects many of his poems, flash fiction, and essays on a website called Wrecks Writes (get the play on words?). He’s also an ordained Universal Life Minister, creating original wedding vows that combine poetry with personal narratives. This year, he was instrumental in forming the first poet-laureate program in Sedona.

Besides improving his writing skills, he credits returning to school with discovering an extended literary world. “I believe the most important part of my later-in-life education was finding and developing a community of writers and, most importantly, readers.” He frequently shares his poetry through workshops and readings, including at the Tucson branch of the Arizona Poetry Society, the University of Arizona Poetry Center, and monthly Sedona Poetry Slams. (“I’m terrible, but hopefully getting better. That is the one avenue where, perhaps, ‘youth’ has an advantage.”) He reads often at various series and open mics.

Rex writes mostly narrative poems with a strong overlap between his fiction and poetry. “I am particularly interested in poetry that tells me a story. I know many people have problems with the obscurity inherent in poetry. No one will likely not understand what my poems are about.” Finding subjects is never a problem for Rex. “I feel like I am always writing. I text myself ideas all the time. If I am ever stuck and need to spark my creativity, all I have to do is search my text history.” His themes are wide-ranging. “I draw from real life, no, fairy tales, no, the natural world, no, my wacky family, no, my dead friends, no. Maybe I don’t have particular poetic themes.”

Lately Rex has been working on an extended project that eulogizes friends who were lost to AIDS. “When I first started writing poems I was motivated to write about my many, too many, young friends who died during the worst of the pandemic. It seemed that most of what I was reading was focused on the tragic death and dying part and not about the fun, living part. My friends had lives and loves that had profound meaning to me beyond their shortened lives. I wanted to remember the good times.”

Rex splits his time between two beautiful landscapes: Sedona and Hawaii. “These locales provide me with a constant stream of inspiration. My neighborhood in Sedona is called Solitude. My property is surrounded by the Coconino National Forest. I am steps away from miles of forests trails and red-rock views. I am never very far from the shadows of those who came before me. I have found pottery shards, arrowheads, abandoned cliff dwellings and Native American rock art. The myths and legends seep into your psyche.”

Rex shows his gifts for authenticity in the following poem. He shares, “I was at a relative’s wedding in Tucson and seated at a back table in the reception. Looking at my tablemates it occurred to me that I was seated at the Sinner’s Table. Ah, great title for a poem ….” Rex’s angle on life and poetry is comic with a touch of tragedy tossed in. By the time we finish the poem, it’s clear that the Sinner’s Table is a whole lot more interesting than anywhere else. In life and in art, Rex can be counted on to “get the party started.”

More at wreckswrites.com

The Sinner’s Table

The six o’clock church wedding

was a somber affair.

The eight o’clock full-moon reception,

not so much.

Like always, I was seated in the back

at what we call the Sinner’s Table.

The Sinner’s Table has

a couple of us gay cousins,

the bride’s one uncle who’s

been to jail a bunch,

the one cousin who’s all-ways

the sloppiest drinker,

our very witchy aunt who

finds the full moon auspicious,

whatever that means,

you know, good or bad,

and then the one older relative on leave

from the old folk's home with zero filter

and shockingly knows all the tea.

There is only beer and soda

at this cheap ass wedding

so, our cousin opens her purse

and pulls out a tiny teacup

and a plastic flask of Old Grandad.

The Grandad part of the label was scotch taped

over with the word tea scribbled in its place.

Our old cousin passed around

her Old Tea in her tiny cup.

We all giggle with pinkies extended

taking sips of ‘tea’ like proper English ladies.

We think this undesirable table,

near the bathroom,

partially hidden behind an ugly pillar,

farthest away from the picked over buffet

of build your own tacos and

the picked over scraps of wedding cake,

is the best table.

We get to watch the other guests

queue for the toilet giving us the side eye

and air kisses as they pass.

The deejay starts with Shaboozey,

as ‘Tipsy’ plays we en masse

attack the dance floor. We can

be counted on to get the party started.

Erik Bitsui is writer, musician, DJ, comedian and all-around headbanger. He describes himself as more than a poet; he’s a poem, as are the rest of us. “We are all walking, living poems. Each one of us is the main character in their own poem. Our life experiences are our unique lyrical lines within the world. Each person’s life is a poetic experience.”

Erik’s poems and essays have been published in Rinky Dink Press, Waxwing Journal, and Defunct Journal. He is proud to be included in The Diné Reader: An Anthology of Navajo Literature. His book, Mosh Pit Etiquette, Volume One: Secrets of a 21st Century Navajo Headbanger, contain essays and narratives that are comic, touching and, as always, poetic.

Born on the Navajo Nation in Blue Gap, Arizona, Erik has lived in Flagstaff on and off since 1982. He attended Northern Arizona University, where he concentrated on engineering till he took an English class, then another, then another. “I am still in contact with many of those same instructors. I always had people encouraging me to tell my own stories.” He then earned an MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder Colorado, an educational course that focuses on writing that is outside the academic mainstream.

Erik performs his spoken-word poetry at open-mic venues in Flagstaff. From his years as a DJ and radio host he developed his narrative voice, a persona that he shares with his audience. “I played heavy-metal music for two hours every Sunday. In between songs I told jokes, shared trivia, relived memories of songs, and performed comedy bits using voice impressions of celebrities. This stream of consciousness flowed throughout my radio show, and I found an interesting voice to work with.” He uses this same technique in his poetry readings now. “When I’m on stage the voice takes over. I might be very nervous and unsure of my direction but, once the spotlight turns on, I go for it. When I perform, I want to give a show for the audience. I want to give them something they may have never experienced before. Performance art using my own writing is truly fulfilling.”

Erik is a founding member of the Northern Arizona Book Festival, an experience he found life-changing. “My literary world opened up. I met Luis Rodriguez. I broke bread with Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison. I met Simon Ortiz and Laura Tohe during this time — they later wrote blurbs for my first book. I introduced Sherman Alexie to a packed house at Procknow Auditorium, then I talked with him as he drove a rental car to Tuba City and Kayenta. I was a Navajo tarantula, feeling everything and talking everything during my time there.”

As a Diné artist, the community of Native American writers past and present is deeply embedded in Erik’s psyche. “I am filled with stories from my own people. Their memories and genetic stories are found within my DNA. When I dream, I share many of the same symbols they dreamt of as well. Coyote is still alive and well and is probably somewhere trying hard to swindle a poor soul. Some Navajo children are seeking their father right now. A young woman became Changing Woman this morning. These cosmological stories are within me, and I see them unfolding every day.”

Erik’s poem “Today on the Rez” is a beautiful slice of life that explores the significance of daily activities, each conveying the weight, comfort, humor, and homesickness of everyday traditions. For Erik, writing is meant to be shared and experienced. “Well, we’re filled with stories, right? We are all filled with experiences and testimonies and poetry. A poem can save lives. A poem can move mountains. Poetry can speak to one person that needs to hear those words. A poem can come along and knock someone out. But, in the end, anyone can be a poet. Poetry is for everyone.”

You can contact Erik at ebitsui@hotmail.com.

Today on The Rez (abridged)

Nali Boy visited us

before he left for the Navy

His Másání made him a bunch of frybread

to take with him

I walked him out to his car

and I gave him

all the money I had

twenty-three dollars and forty-five cents

Aunty ate three slices

of Sonny Boy’s birthday cake

then she drank two cans of pop

Then she took her insulin shot

We wanted to chop wood

but we couldn’t find

the axe and wheelbarrow

so we had to hike through the deep snow

to my other grandma’s house to get them back

Last night on the rez

Uncle and Grandma drove all around

until ten o’clock looking for the sheep

because me and my cousin

forgot to bring them back

We thought it was OK

but Grandma got worried

so Uncle took her looking for them

Me and Cousin stayed behind

We watched Uncle’s truck headlights

going down one way

then up another way

They weren’t even using roads

Uncle’s truck just rolled over sagebrush

Aunty called my mum on Saturday

She said she got a hotel room in Chinle

so my mum drove me and my sister

over there to swim with my cousins

We swam all day and had a lot of fun

My mum and Aunty just sat by the pool

They talked and laughed

When we finally drove home

my little sister fell asleep

with a bag of Cheetos on her lap

When I got home

I sure fell asleep real fast

because I was all tired

When I went to school

I smelled like smoke and mutton

that’s because we butchered at my grandma’s house

The silly janitor at school said to me

“Hey son you smell like a rich Navajo”

No one laughed just him

Then he said it again and laughed some more

all by himself

My teacher fell asleep in class again

She falls asleep because

she takes care of her dad

She told us kids

her dad is old and can’t take care of himself

so he lives with her

She said no one else will take care of him

Whenever she falls asleep like that at her desk

our class stays real quiet

and we just let her sleep

This weekend

I sang for the first time at a peyote meeting

I’ve always liked the four songs I sang

My uncle and I practiced them

for a long time before I sang those songs

After the meeting was over

Uncle came up to me

He hugged me and said he loved me

He gave me twenty dollars and told me

“Keep Singing”

Full poem: https://www.noazbookfest.org/e-bitsui

Chelsey Burden writes about landscapes, both outer and inner. “In my work, the desert landscape comes up often, and I’m usually writing about the emotional landscape of issues around autonomy, sexism and mortality.” Poetry becomes a means to reconcile the internal and external points of view. “The boundary between the two feels very nebulous and permeable. External images act as a reflection for internal experiences that would otherwise be invisible.”

Chelsey’s poems have been published in many journals and she is the author of a poetry chapbook, Thorax Carnival from Dancing Girl Press. Her poem “The Girl Among the Geese” won Vocal’s After the Parade prize. She received an MFA in creative writing from NAU after completing BAs in sociology and women/gender studies. “I’m very curious about why society functions the way it does, and I wanted to get a deeper understanding of social problems to then figure out how I could best be of service.” That led to her work in libraries over the past 15 years.

Writing, though, has always been a part of Chelsey’s life. “I wrote poetry from age five or so. My parents read to me a lot and really encouraged early literacy, which is one of the best things you can do for your kids. I’ve always been highly sensitive, so I appreciated the comfort of the written word, and then being the one doing the writing gave me a sense of agency and self-connection.” She even discovered an early poem written in the second grade: rattlesnake waits quietly / SNAP! / It strikes poor rabbit. / Then all is quiet again. She adds, “I haven’t changed.”

Chelsey finds poetry to be both personal and universal, private and public. “If I think too much about the reader, inspiration eludes me and the writing feels flat and forced. But if I don’t consider the reader at all, what connection am I offering? The poems I feel best about began as very private and personal, but then were edited with an awareness of the reader.” The most successful poems act as conduits between writer and reader. “Poetry is transformational. It’s a bridge between people, a direct line between hearts.”

Chelsey’s roots are in the Mohave Desert. “I grew up in Kingman, then moved to Flagstaff when I was 18 and stayed there till I was 31. I love the mountains and forests of Flagstaff so much.” She now lives in Minneapolis, where she works at a children’s-book publisher. “I visit Arizona a few times a year, and it will always be my home.”

Inspiration for new poems can turn up anywhere for Chelsey. “A recent poem, ‘Ode to My Apartment Neighbors,’ came as a knock on my door letting me know/ the washing machine is now open. It emerged as I reflected on the connective tissue of people who live in close quarters. Especially in this digital age, I think a lot about community in the sense of the people physically around you.”

“I’ve always loved Sylvia Plath. She seems to give real weight to female pain in a world that doesn’t take it seriously. Mary Oliver offers so much comfort by naming what’s already waiting in the natural world. Andrea Gibson is so accessible to so many people, which is something I admire.”

In the following poem, “Litany of Lovers and Weather,” Chelsey expands on her theme of landscapes. “The external and internal landscapes naturally speak to each other. It’s especially apparent when two people’s internal landscapes are externalized in a clash of some sort. The wreckage left behind by people reminded me of storms and vice versa.” She feels that poems in general tap into many subconscious associations. “Imagery enters as a language of its own, especially when personal emotional language is inaccessible to the individual. Religious imagery emerges often. I think it’s the symbolism the collective unconscious is swimming in.”

Ultimately for Chelsey, poetry is a way to find common ground with others. “At weddings and funerals, people turn to music and poetry. I think these forms are ancient and applicable to all people, and they are there for us during the most emotionally intense times as an anchor, a guide, a comfort.”

More at chelseyburden.wordpress.com.

Of course we are storms, passing through

the landscapes of one another.

How else would that bottle

have turned into glass shards, triangular

and scattered like shining confetti?

How else would those sheets have become

soaked through? From the salt and water

of the sweat of the body or

deliverance from black rain clouds.

How else would that drywall have borne

holes? Debris white as knuckle bone.

Or consider the creation

of crow’s feet on flightless faces

and crooked lines of furrowed brows,

deepening with repetition, etched

like washes in the desert.

Of course we are storms and landscapes.

How else would the blood of others

have come down on me in droplets?

Like the storms that have lifted up,

then torn apart, frogs and catfish,

carried their remains through the air,

like a funeral procession.

How else would old letters

have ended up in the trashcan?

Or like the storm they say poured out

periwinkle and hermit crabs:

the consciousness of someone else?

fragmented, shaken, raining down.

Of course we are storms and landscapes.

The dawn after the storm has passed,

these memories litter the land,

hanging exposed, raw broken nerves.

The snapped branches, the fallen trees,

the puddles that gather and cling.

The clouds that fade like old bruises.

The dark wet tint of roof tiles

and pavement, dampened as if with

watercolors. And most of all,

the soggy earthworms who emerge,

lengthening their pallid bodies.

Murmuring yes, we have smelled death.

And we’ve eaten it.

You can name us resurrection.

Happy Heavenly Oasis has a vision: she would love for everyone to be happy. Really happy. Blissed-out kind of happy. She founded Blissology University, where “budding Blissologists” can learn the secrets to inner joy. To that end, she has written two books, Bliss Conscious Communication, which is guaranteed to raise your “conversational kundalini,” and uncivilized ecstasies, featuring poems celebrating the joys of living outside civilization — namely, life, nature, inner peace and, of course, bliss.

Happyo (her nickname) lives part of the year in her self-designed haven and wildlife sanctuary, “Prescott’s Paradise in the Granite Dells,” Heaven on Earth Retreat, a popular staycation and getaway that draws guests from around the world. The rest of the year Happy and Free, her beloved, explore the planet. She describes herself as an “ecstatic nomad, an adventure anthropologist, succulent strategist, ethical adviser, environmental advocate, wilderness guide, community-solutions leader, eco-entrepreneur, songwriter, performer, volunteer, naturalist, health and happiness consultant, and poet.”

For Happyo, poetry is a “hiking trail to enlightenment” that started early in life. “At age twelve I began immersing in a multitude of meditation techniques while also studying oriental philosophy. Later, I delved deeply when abiding for years at dozens of ashrams in India and monasteries in Thailand. Consequently the ecstasy of ethics, everyday mysticism, and living awareness of the invisible world ceaselessly vibrating all around and inside us flow through the poetry too.”

Happyo feels that poetry allows us to tap into a childlike innocence. “Poetry is a return to play. When was the last time you danced in the rain or simply rolled on a lawn or did something truly hugely daring? Playful, pure-hearted poetry invites us to return to our inner knowing. It allows us to see the world with fresh eyes, to evoke the bliss body, Walt Whitman’s ‘body electric,’ the exhilaration of being alive!”

She compiled the poems in uncivilized ecstasies over a number of years, living and backpacking internationally. The book is self-published, which Happyo considers “a poetic act in itself that offers any poetical artist the ultimate freedom to not only express most exquisitely and truthfully, but also to be innovative with other artistic aspects, from photos to fonts, art to binding, and all the other delicious details of creating one’s own book.”

Things weren’t always so blissful for Happyo. As a young adult she survived several armed conflicts overseas and lived through the worst of the famine in Bangladesh. But her joyful nature and research into happiness reached new heights during her anthropological adventures. She was “adopted by seven tribal families, in seven remote, off-the-grid locations in seven countries over seven years,” where she learned these tribes’ joyful ways of being in the wilderness.

In memory of a close friend in high school who tragically suicided after years of writing negative poetry, Happyo made a commitment to create poetry that enhances gratitude and inspires uplifting reflections. “Poetry can arouse wonder and delight while activating the miraculous. Most of all, poetry is a profound portal to meditation, contemplation, humor, beauty, silence, celebration, serenity, epiphanies and spiritual realization.”

The untitled poems here carry insight into Happyo’s frame of mind during her adventures. The first offers “precious glimpses into India back in the 1980s. I loved being a trekking guide, grateful beyond measure to lead long-distance intercultural backpacking adventures in the Himalayas for decades with wandering monks, sadhu and local alpinists.” The next poem was written in an historic lookout cabin on a rocky summit. “I treasured four blissful summers serving as the resident Hyde Peak fire lookout for Prescott National Forest while breathing in the vastly beautiful, panoramic silence.”

Happyo hopes her poems will touch others far into the future. “Our poetry best be perennial and true so that some poetic soul can read it a thousand years from now, laughing with the humor, wondering aloud, and personally relating in deeply heartfelt ways.”

But for now she encourages others to participate fully in artistic expression. “Let’s activate the miraculous as we Bliss Forth with Love.”

More at happyoasis.com.

god comes to me in taxi stands

in the smile of a child with outstretched hands

she toils with shyness, her eyes avert

then dares “namaste gi” wringing her skirt

through the eyes of a child hush treasures untold

in this girl’s soft glance, it’s god i behold

god comes to me in a persimmon tree

where old crow cackles and caws

i cackle back to this black-feathered jack

to whose song i render applause

god comes to me in a ridgetop hut

high home to gaddhi shepherds and sheep

glad slapping hands in chapatti lands

with chai, song, then fireside sleep

god comes to me in glacial peaks*

like sets of teeth against the sky

in the rose of dawn my heart is born

om nama shivay

*of the Himalaya

i long to be with you at dawn

as our ears first awaken

to silver raindrops singing

upon the roof

to the chubby kettle humming

breathfully then

clearing its voice in a

high-pitched triumphant operetta

to the cactus wrens

flitting excitedly

among dewy junipers

i long to be with you

as our eyes softly open

to sunlight beaming

through cherubic clouds

splashing our lashes

twinkling grinning gathering

love

i long to be with you

morning after morning

You can usually find writer James Jay behind the bar at Uptown Pubhouse in Flagstaff. He may be serving drinks, but he’s thinking about poetry. “Conversations with regulars and strangers alike provide loads of potential subjects and situations to write about.” He’s certainly made the most of his barroom experiences. For years he wrote a column for FlagLive called Bartender Wisdom. His third collection of poems is called Barman, and he’s just published another collection through Foothills Publishing, Whiskey Box.

Bartending is only part of James’ life though. He has an MA degree in Literature from Northern Arizona University, and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Montana. He’s taught poetry in public schools, jails, colleges and universities. He also served as president of the Northern Arizona Book Festival for ten years.

James’ poems have a thoughtful economy of words, a poetic realism that touches on and elevates many everyday topics. “Anything can be a poetic source of inspiration. Anything can be a treasure.” He’s continually receptive to new ideas for poems. “I always have a journal and pen with me. I dash down things, a lot of which I never come back to. The act of scrawling helps keep me motivated, however. When I do return to those words it becomes a scavenger hunt, a sifting and sorting. I love finding these artifacts. It’s through the act of writing the poem that they become something else. It’s then, if all goes well, that I can make the real discovery and stumble into thoughts or feelings or ideas that take me by surprise. Nothing into something.”

Arizona’s high-desert landscape has a strong influence on James’ writing. “My dad was in the Army and we bounced around a lot, but Kingman is where I ended up for the longest period. That desert I played in as a kid, with its creosote, mesquite, tumbleweeds and distinct, precise vegetation, shaped the pace and way I like to see things, smell things, experience the world. That permeates my writing, regardless of the subject or location.”

He’s lived in Flagstaff for many years, but also spends time teaching poetry for the Missoula Writing Collaborative in Montana. “It’s hard to imagine living anywhere else than the West. I enjoy visiting lots of different places, but the West is home. My wife Aly is an ultrarunner and knows miles and miles of trails in Flagstaff and throughout the Coconino and Kaibab forests. My sons Wilson and Henry have been cutting firewood with me since they were little, and they dig anything outdoors. We have three rez dogs, and during the pandemic we fostered dozens of pups with parvo. All this informs everything I write, what I’m interested in reading, and where I keep my attention and focus.”

Sharing poetry through teaching is fulfilling and inspiring for James. He finds that poetry acts as a great equalizer, no matter the locale. “A sonnet, whether at the university or high school or jail, is a sonnet. The ability to listen to and communicate with a host of people becomes essential, and the poems do the heavy lifting in this task.”

Like teaching, his experiences with Northern Arizona Book Festival have been rewarding. “It was an honor. I was able to meet some of my literary heroes, like Robert Bly, Dorothy Allison, Tim Seibles, all of whom are tremendous ambassadors of poetry and literature. I tried to get as many up-and-coming writers

and mid-career folks into the festival as well in hopes of connecting with the audience. You never know which writer will speak profoundly to someone. I’m thrilled to see it still going strong and pushing into its third decade.”

James shares the history behind the following poems. “I’ve written hundreds of Whiskey Box poems over the years. When I’m working at the pub and breaking down boxes for the recycler, I’ll sometimes pull interesting boxes aside and write poems, sonnets, notes or letters on the backs of them. Mainly I mail them out to folks. I don’t generally keep any copies. Mostly I remember them, kick them around in my head, and then revise the ones I like and shape them into poems.”

For James, poetry’s recurring beauty continually amazes him. “Lines I’ve heard or read decades before come back to me at various times. Whether it’s on early mornings walking the dogs, during conversations with old friends, or waiting to checkout at the grocery store, I find lines of poetry return to me, oftentimes as powerful as when I first read or heard them. I love poetry’s endurance.”

More at foothillspublishing.org/james-jay

I found first the scanned arrest record

for my great grandpa

through the genealogy research

to which I subscribed monthly.

Bad check writing. Sixteen years old. Nebraska.

The family had come down on tough times.

He only found the ledgers, claimed his confession

to the court. It’s not like he pilfered firsthand.

Buy of this what you want.

He’s not my great grandpa anyway.

He’s yours. Your family had come down

on those old and familiar tough times.

Whatever makes you feel better, keep.

The rest toss back, so many tiny fish hooked

on a wide sea of bad luck. You passed those bum

checks, so you’d be in a tale, whatever the role.

Because you went quietly, the sheriff kept

the cuffs loose. This evidence is my record.

The box of Talisker 10,

go inside

with your fingers

and pull up a flap.

There, there rests

Richard Hugo’s lines, not Scottish at all.

Wide forehead

like a Cadillac,

mechanic at Boeing,

forever American,

he spent time on Skye

jotting notes in journals.

Press them, map-flat,

and be content as a fellow

moved to dayshift.

For the Guggenheims,

he fired off poems

for a book. For you,

he left words

elsewhere,

cast onto currents of the sea —

We are what we sing.

For Arizona poet Alfred Fournier, grief touches many of his works. Whether he is writing about family, the environment or spiritual concerns, a feeling of loss is never far from the surface.

“My family poems initially arose out of a need to explore my memories surrounding my mother’s illness and death when I was a child. It expanded from there to poems about my siblings and our relationships.” These family poems allow him to reimagine his past. “I feel I am mythologizing our family story in these poems, which are fact-based, but seen through the lens of poetic imagination.”

His poems about the environment reflect a similar emphasis. “These poems are really an exploration of ecological grief. . . . So much has been put at risk by the lifestyle we’ve pursued for centuries now. Through imagery, personification and wild flights of imagination, poetry invites the reader to look at these issues in a new way.”

Questions of spirituality also infuse much of his writing. “It works as a subtext through many of the poems. I suppose it is because I’m always searching for some kind of higher meaning behind things.”

Alfred’s poems and short essays have been published extensively in noted journals. It took about five years for him to collect and assess the poems included in his book A Summons on the Wind. “I knew from the start I would have two sections, one more focused on the outer world (environmental and social issues) and one highlighting primarily family poems. For each section, the trick was what to include, what to leave out, and how to sequence them. I spent a lot of time on this, and it was great fun. Quite a few poems I really love were left out of the book because they just couldn’t find a place to sit comfortably with the other poems. I think the book is better for what I left out.”

Alfred’s essays are primarily short nonfiction, with much stylistic overlap with his poetry. “Whether I go with poetry or prose, the most important element for me in developing a final piece is the sound. I tend to use off-time internal rhyme and assonance to help the flow of a piece, much as I would with poetry. It has to sound good when read aloud.”

Alfred began writing as a teenager, but did not return to writing seriously till seven or eight years ago. “I connected with other writers locally and started reading contemporary poets. That was life-changing.” Now he writes every morning. He lives in Ahwatukee, in the southernmost portion of Phoenix, with his wife and daughter. “I rise to write before the others get up. This is My time, and I try to honor it no matter how hectic the workday ahead. It grounds me.”

He doesn’t have expectations of an end result when he writes. “I generally approach the empty page with no plan at all. Sometimes I journal, sometimes I start right off with a poem. I might reflect on something I’ve been reading, and those reflections can lead to a piece. A high percentage of what I write is not geared toward a final product.”

Alfred volunteers with Connect and Heal, a Chandler-based nonprofit that runs poetry workshops and readings. “They're dedicated to the idea that when people plug into the power of artistic self-expression and cultural exposure, it can result in therapeutic healing, personal enrichment, and positive social support.” These workshops and other local readings allow him to share his work and help motivate him creatively. “As much as I love poetry on the page, it’s great to be heard and to respond to the work of others. I always do some of my most inspired writing the morning after a good poetry reading or open mic. Just hearing the work of others gets the juices flowing.”

In “Warning!” Alfred employs exaggerated imagery to emphasize the threat of ecological disasters. “A baby in the crib sprouts mandibles and wings and flies out the window with a restless desire to reconnect with the natural world.” In “Drywall” he reminds us that sadness is constant in our lives, often right next door. “We have to experience these lows, the dips, so that ultimately we can rise, becoming the best of ourselves. Grief, in part, makes us who we are.”

More at alfredfournier.com.

Do not feed honey to infants under one year.

They may give up the breast.

They might sprout mandibles and gnaw

the crib rail restlessly, fly from the window

with a craving for wildflowers

and forsake human form.

And who can blame them?

Distillation of floral nectar gathered

in a million flights of drones, passed

mouth to mouth — whole societies

ordered around this purpose — to hover,

to taste, to fly, pollen-laden legs

dusting the air, trailing back to the hive.

And isn’t this how humans began?

Community and kin. Returning with food

to nourish our young. Stories ‘round

the firelight. Cherished home among

rivers and plains, before we got the taste

for nature as commerce.

A memory this deep becomes a danger.

Do not feed honey to your infant.

They may become famished

for a world long gone, waking up hungry

in a place where nothing is sweet.

(First published in Gyroscope Review)

If you knew your long-dead mother was sleeping

in the hotel room adjacent to yours,

not in the wind-swept hills of her girlhood,

nor some grim castle tower gnawed by rain

into a state of decay, but just beyond thin layers

of drywall where every sound you make

reverberates,

would you step more tenderly

across creaking floorboards, lower the volume

on that 360 speaker you take everywhere,

keep the TV news to a whisper? When you wake

in the famine of night, residue of childhood fears

brooding like a dark forest inside you,

place your palm flat against the wall. Listen

for the bounty that lives within silence.

Let sorrow dip and rise like a nighthawk inside you.

(First published by Poppy Road Review)

Poet Sharon Suzuki-Martinez finds inspiration in unlikely places. Her writing covers diverse topics, from Sasquatch to ethnozoology to In-n-Out Burger, combining a mix of playfulness and gravity. “No matter how much I brood, absurdity always breaks through the darkness like dandelions through a sidewalk. With me it’s all about balance.”

Sharon’s poetry and essays have been widely published. Her latest book of poems, The Loneliest Whale Blues, winner of the Washington Prize, received rave reviews. She is a Kundiman Fellow, a Best of the Net finalist, and a Pushcart nominee. Her next poetry collection focuses on the internet and includes found poems pieced together from various resources, including social media posts, Yelp reviews and Google Translate. “This is very exciting for me because I am not aware of anyone else using social media in this way.”

Sharon chooses topics that fascinate her. “I obsessively research something that puzzles me to see its wider context and stumble across odd facts, connections and tangents. I want to thoroughly understand the mysterious thing to articulate its wonder to others.” A few of her recurring themes include: “What appears to be a single thing is made up of many smaller things, and what looks like many small things (no matter how disparate) are actually one thing; staring at the mundane until it becomes magical, and the reverse, letting the strange become familiar; the ambivalence of monsters — our wonder and dread evoked by mysterious creatures and people dwelling in the margins, at the borders.” She relishes these deep informational dives, feeling that condensing the exploration by using apps and AI “would be like taking a short cut rather than the scenic route.”

Sharon is of Okinawan/Japanese heritage, grew up in Hawaii and moved to Arizona to earn her doctoral degree. Although she considers her cultural background “the air I breathe,” she does not write specifically about herself. “All of this is influential on my point of view, but rarely the inspiration or main topic of my poems.” She has written many haibun, a traditional Japanese form that combines prose and haiku. “I wish I could say that I was taught to write haibun by my grandmother to continue our ancestral tradition, but I wasn’t. I’m the first writer on both sides of my family. Nevertheless, writing a haibun makes me feel like I’m honoring my ancestors. Also, the haibun feels like home, a place where I can be run-off-at-the-mouth candid, but also introspective and concise. It is where I can truly be myself.”

Moving to Tempe had its challenges for Sharon, including a stereo-blaring apartment complex, crazy hot weather and constant traffic, but “the comic absurdity of my situation eventually took over so I could write poems.” The two haibun on this page demonstrate Sharon’s skill in merging prose and poetry, humor and pathos. In “Taco Shop Haibun” she learns to transcend the outside world at a Mexican fast-food joint. “It had a peaceful vibe, like being in the desert wilderness instead of a crowded metro area.” She wrote “Snail Haibun” after discovering a couple of interesting facts about snails: they choose their companions, and they eat their dead. “I love all animals and so I live for info like this. These odd, easily shattered creatures connected with me through kintsugi.” Ultimately, writing allows Sharon to examine many sides of existence and offers solace from dark feelings. Hinting at the ravages of propaganda, she shares, “Poetry is the best medicine for despair induced by lies. So, while most Americans won’t make time for it, poetry waits like a healing scenic route home.”

More at sharonsuzukimartinez.com.

Slow. Slower than a tortoise chewing a Milk Dud. Here, it feels like time immemorial in the desert rather than the middle of asphalt Arizona. Our apartment is just a kiss away from major crashroads and “Los Fav’s,” the strip mall hole-in-the-wall. The past lunch hour has seen landscape crews, suits, moms, Sun Devils, and missionaries. Norteño music drifts from the kitchen into the dining room decorated with a pool table and vending machines stocked with instant tattoos and soul patches. I tuck into my crunchy beef taco combo and watch the traffic beyond the glass storefront. Soundless traffic is as lulling as watching goldfish. Goldfish in SUVs and pickups, swerving and flipping each other off. A stone’s throw away in the parking lot, the wind almost turns the page of a newspaper stuck under pink oleanders.

Amidst the rat race:

pockets of eternity,

refried beans and rice.

There is a humble snail inside my chest. Thrift store white porcelain shell. Eyestalks glancing the clouds like kite strings. It learns slowly, but it never forgets. I used to smoke to force my snail into its shell. So it couldn’t see, so I couldn’t feel. Now I can make my heart hide in its shell without cigarettes. But cynicism is brittle armor. Life will still crush you, and march on. And since nothing in nature is ever wasted, other snails will eat you, and crawl on. But more often than not, life has put me back together, shard by shard. We all can be brutal boots, but also helping hands. It also helps to know about kintsugi, a Japanese art form meaning “to repair with gold.” When a ceramic piece breaks, a craftsperson rejoins its parts using lacquer dusted with gold or silver. These lustrous scars render the pottery even more beautiful than when it was perfectly intact.

The greatest treasure

could be one’s humility.

A fractured heart, healed.

“Taco Shop Haibun” first appeared in Four Chambers; “Snail Haibun” in Anti-Heroin Chic.

For Flagstaff writer Laura Adrienne Brady, poetry has unlimited potential. “It is a space where anything can happen. I have the sense of entering some kind of intuitive ceremony or improvisational experience.” Laura is also an essayist and the singer-songwriter known as Wren. She finds that each creative outlet has unique characteristics and opportunities. “A song lets me control the emotional tenor for the audience. An essay is a guided journey of ideas. A poem is looser, a series of images and impressions. I have less control over how it touches you or where it takes you, and that’s part of its magic.”

Laura’s writings have appeared in many publications and won nominations for a Pushcart Prize and The Best of the Net. She has released three albums. Her poems interlace a deep reverence for nature and a mission to support strong social and environmental ecosystems in art and life. “The most consistent theme of my work across all genres is probably humans’ connection to the greater-than-human world. Though the earth may at times appear to sit at the background, I think it is almost always a character in my pieces.”

Laura came down with a complex chronic illness in her mid-twenties. This has a profound effect on her life and writing. “Illness forced a painful yet necessary rounding out of my personality, and changed how I experienced the world around me. My life slowed way down. I could no longer plan for the future; my plans so regularly fell apart due to my body’s limitations. I began to learn to live in a smaller and more immediate way. I felt cast out of the whirring, capitalist pace of life, as well as the typical pathways to career success and financial stability. Initially, this felt like a great injustice. With time, I’ve come to see the casting out as a deeply inconvenient blessing.”

Laura received an MFA in creative writing from Northern Arizona University. She currently teaches writing at the college level plus online creative-writing classes and coaching. Her personal writing schedule varies over time and seasons. “I’ve had periods where I schedule writing time three or four mornings a week and sit down to work even if I’m not in the mood; phases where I don’t need any structure because I’m writing on a flood of inspiration; periods where I’m only revising and refining older work; and phases that feel more about living, taking notes, and going on lots of contemplative walks, rather than being ready to make something. By the time I actually write anything, I’ve usually already spent hours musing on the topic while going on my daily walks in the woods.” This lesson extends into her teaching. “I like to remind my students that most of the writing process isn’t actually the writing part! It’s the living and thinking and digesting part that occupies perhaps 75% of the time.”

Laura uncovers ideas for poems in two ways. “The first is with a phrase jotted in a notebook, a simple line that captures something big I want to express, but that won’t be impactful on its own. In those cases, I then must write the poem that prepares the reader for that line. The other way is with an imagistic story or scene that’s been guiding me to understand something about my life or the world. Usually through fleshing out what that scene looks like, feels like, smells like, I find the poem that wants to come through.”

The local environment and community of Flagstaff provide continuing inspiration for Laura. “Flagstaff is a truly special place. When I visited for the first time I wasn’t immediately enamored by the cloudy skies and lack of color of that particularly gloomy weekend. But I felt so welcomed by the writing community that coming here felt like a huge and immediate yes! Because my poor health kept me often at home, it’s been a slow-building love affair with the area. However, as I get stronger each year and can roam farther into the aspens and prairies, my love for the place grows in leaps and bounds, and this truly feels like home now.”

In the following poem, Laura draws parallels between a childhood memory and the challenges of her illness. “One of the only ways I’ve found to regain power when powerless to feel better is to create meaning and beauty from the experience of suffering.” She feels that her writing skills have grown over her career. “The gap between the ideal poem in my mind and the poem I actually create is narrowing (though still never quite achieved!). The striving to translate imagination to reality is perhaps the fuel that pushes me forever onward as a creator.”

More: lauraadriennebrady.com

If lost, the camp counselor instructs, you must wait

to be found. My friends and I nod and then howl,

eager to scatter, make mischief like puppies. I will

always recall this advice and have not yet

found it to be true. In st/illness I draw myself

closer—every extra limb falls away, fingers

gone to roots, bones turned to stone. When

they gather my hair decades later, they will laugh,

let it go, embarrassed. This is no woman —

just fallen usnea. Even if I vibrate and shake, and

bluebirds erupt from my chest, still I will not

be seen. I have stopped believing anyone

can offer me a cure I do not already carry. I outstretch

my hands and they remain empty. The map writes itself

from the direction I turn — distant routes

crumble like fallen tunnels; choices split like ripe

peaches and new ones emerge in their place. Always

the beetles march in, waving the banners of hunger.

There is beauty to make from rot and shards, from

golden bees that crawl from nostrils and ears,

trailing honey. Every bit of sweetness in this world

matters. I once traveled all the way to the northernmost

edge to remember the look of love on my parents’

faces. The last choice I have is the song I sing to myself.

This poem first appeared in A Body You Talk To: An Anthology of Contemporary Disability from Sundress Press.

Don’t be surprised if the next time you’re folding towels at the laundromat, Shawnte Orion stops by to share a few poems. He’s read in unusual locations — hair salons, laundromats, between bands at bars — spreading the word about poetry and pushing the limits of where poetry belongs. “Poetry shouldn’t be relegated to universities and classrooms,” he says.

Shawnte’s bio reveals that he attended Paradise Valley Community College — for one day. His personal poetic education is a combination of his unique view of the world and the influences and inspirations of popular and classic culture. “Although I didn’t go to college, my formative years and aesthetics were shaped by things like music and cinema. In hindsight, there was always a poetic core at the heart of my favorite songwriters, filmmakers, and comedians.”

Shawnte has published three collections of poetry, his latest called Gravity & Spectacle, and his work has appeared in many notable journals. Besides laundromats he performs often in local bookstores and cafes. Over the past few years he has joined the editorial team at indie publishers rinky dink press, whose mission is to “get poetry back in the hands (and pockets) of the people” by printing inexpensive micro-collections. This role has allowed him to discover and showcase new poets. “It’s been a rewarding experience to work with other writers and help portray their vision. I enjoy creating cover art and introducing readers to our authors when we set up tables at book fairs and conferences.”

Shawnte also appreciates creative partnerships with other artists. “Writing is mostly an isolated, lonesome pursuit, so it’s been exciting to venture into some collaborative projects over the past few years. Gravity & Spectacle was created with photographer/poet Jia Oak Baker. Then I had the opportunity to do a vinyl record with the San Francisco band Sweat Lodge. A musician friend, Robbie Cohen, added amazing soundscapes to my poems, and we got a great montage from Bay Area artist John Vochatzer for the cover. It was thrilling to see everyone’s work come together to create something greater than I could have ever manifested on my own.”

Shawnte’s poetry has the ability to elevate the ordinary into the extraordinary, uncovering deep reserves in day-to-day situations. His work can be both funny and aching, often within the same piece. He finds that poetry is unique in its ability to communicate much in only a few words. “My high-school French teacher used the poems of Jacques Prévert for us to translate and recite. I was captivated by how efficiently ideas and experiences could be conveyed through concise and quickened language.”

Shawnte says that his understanding of his own work expands when shared with others. “Live readings are rare opportunities to interact with an audience. When something gets published, you don't know if anyone ever ends up finding and reading it. It's just out there somewhere in the void. But getting to share poems in front of a crowd gives you a real-time glimpse of how people react to your work. Especially in this age of constant distraction, where everyone has a steady stream of text messages and notifications, it feels subversive when you and a room full of people suddenly click and connect enough to stop checking our phones and be present with each other for 20 or 30 minutes.”

The following poem succinctly captures the Arizona heat in short bursts of imagery. If you’re wondering about the title, Shawnte explains, “I always liked the mechanics of portmanteau; the melding of two words into a new term that blends their meanings (‘spork’ and ‘brunch,’ for example). So, the title is like a portmanteau, but with numbers. The area code for Phoenix is 602, and since it can be hot as hell, it felt natural to combine it with the biblical number of the Beast.”