When in 2022 the Arizona legislature passed a law requiring that voters prove their citizenship to be able to vote in state and local elections, enforcement was delayed by court challenges till 2024, when the US Supreme Court upheld it for the following election cycle.

Driver’s licenses were expected to be the main source of identification, but some were issued so long ago that the Arizona Department of Transportation’s Motor Vehicles Division records didn’t require that information.

The Secretary of State’s office discovered that 200,000 people statewide lacked the required proof for their driver’s licenses, many because they were issued before modern computer systems existed.

Yavapai County Recorder Michelle Burchill says that the Secretary of State’s office identified a total 11,058 people without proof of citizenship proof in the county. Even some workers in the Recorder’s Office were shocked to find their names on the list.

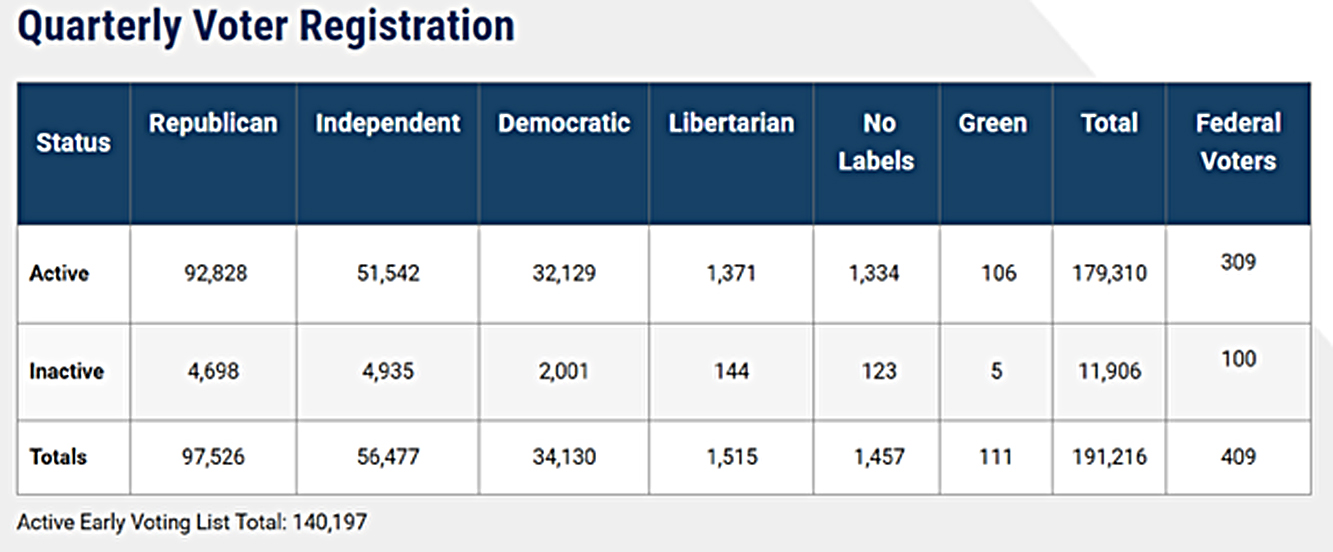

After eliminating those who had moved or died, the number of uncredentialed voters totaled just under 10,000. On the original list the party breakdown was 5,827 Republicans, 1,958 Democrats, 82 Libertarians, 60 No Labels, 4 Greens, and 3,127 Independents.

Starting in April the Recorder’s office sent letters to those voters. Since then a little more than 30% (about 3,000) people have proven their citizenship, and a few come in daily to do so, says Burchill. They must provide a birth certificate, passport, tribal ID or naturalization papers to qualify.

“We’re hoping, with all the pressure around the country for getting Real IDs, that people will update their driver’s-license registrations and become eligible that way,” Burchill said. About 500,000 have already done so, and soon Burchill said she will ask the Secretary of State’s Office to run the numbers again so that some will drop off the list automatically.

Although some county recorders have said they would remove voters who haven’t responded after an arbitrary period, Burchill said there are no guidelines in the statutes for a waiting period, so she won’t do so without guidance from Attorney General Kris Mayes, whose office will issue a ruling soon. “We’ll do a follow-up letter with a deadline when we have one,” Burchill said.

The office has received calls from some voters asking whether the letter was legitimate and why they were singled out. “We had a few people who responded who were upset, and I had a real nice love letter from someone in Sedona,” Burchill said, commenting that it contained colorful language. “We tell them that we’re just trying to make sure our voter rolls are as up to date as possible.”

Keeping track of voters is one of the major tasks of the recorder’s office, which has now been further complicated. “An average of 300 voters per week update or change an address,” Burchill said. “It’s a churning list, we see it change all the time.”

While Yavapai has been judicious in its approach to removing voters, some counties are less so. Voter purges have been common. A group called Protect Democracy found that between November 2020 and August 2024 Arizona removed or inactivated about 1.7 million voters, or 26% of its voter rolls.

A 2024 study by the Brennan Center for Justice found that the voters who have been most affected by voter purges are young, located near colleges, and those concentrated on tribal lands. Young people, according to other studies, are more likely to be removed from voter rolls because they move more frequently than people who have stable housing, such as home ownership.

Now that it’s easier to update voter information online at the AZMVD website, voters who have already proven citizenship can simply change their address when they move. Anyone can check their voter registration status on the Secretary of State’s website.

More effect on Native voters

A story in The Guardian reports that in the 2024 election Native American voting was negatively impacted by several ongoing problems. Ballots weren’t delivered because of streets lacking names, polling sites in Apache County didn’t open on time, wrong ballots were being printed, and some voters were discouraged by long lines from voting in person. Non-tribal IDs were rejected at some polling places, and language issues affected access.

In general, turnout on tribal lands has been 11-15 points lower than in non-reservation areas. Native Americans comprise 5% of Arizona’s vote. The difficulty in getting IDs because of their remote locations has meant that the highest concentrations of federal-only voters in Arizona are concentrated on tribal reservations: Navajo, Hopi, White Mountain Apache, San Carlos Apache and Tohono O’odham.