WHEN PEOPLE THINK of the homeless they usually picture men, often veterans or those with addiction issues, living in encampments or cars. Housing analysts point to another group at great risk: senior women.

In 2025 local advocate Shea Richland approached the Prescott City Council to describe the problem, which was also outlined in the State of Housing in Arizona 2024 report by the Arizona Research Center for Housing Equity and Sustainability (ARCHES). Older adults are at risk of housing insecurity because of rising rental costs, additional healthcare costs and fixed incomes that can’t keep up with increases. Women make up the majority of elderly individuals living alone.

Richland points out that because older women were paid less than men for most of heir careers, they’re also usually in more precarious positions even if they worked full-time. She counts herself among the vulnerable as an older retired woman.

“I think it’s a story that needs to be told because, I mean, I have felt this way,” Richland said. “I have been embarrassed and ashamed about my circumstances. I put myself through college, I’ve been in marketing and management positions, I have a higher education, and I have opened my own practice. I’m a capable woman, and here I am. It’s not to say that I haven’t made a decision or two in my life that probably should have been different, but so many of these women are embarrassed and ashamed. Somehow they think it’s their fault that they’re where they are.”

Richland cites the Lilly Ledbetter Supreme Court case as an example of how women were routinely paid less than men after they entered the workforce in large numbers during the 1960s and ‘70s. Ledbetter sued her employer, Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., for underpaying her compared with men in the same management roles. She earned $2,000 per month less than men in the same positions. The Supreme Court ruled that she would have had to bring the case within 180 days of the date of the discriminatory policy being enacted. Congress passed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act in 2009 to extend that timeline requirement.

The Census Bureau reports that as of 2024, female workers earn 83 cents on the dollar compared with male workers. In 1982 women earned 65 cents on the dollar. That gender-pay gap has stopped closing by more than a few cents since 2002.

“I want women to get angry, and I want women to face the truth,” Richland said. “This is partly about our society and women being treated as second-class citizens from the time they take their first breaths, let alone their first jobs.”

Even widows who have income from a spouse’s pension or Social Security may find it’s not enough to live on in their later years, especially as healthcare costs mount. Those with mobility issues have fewer options for accessible housing, according to the 2024 housing report. Census Bureau statistics also show that the poverty rate among Arizona seniors (65+) is higher among women than men.

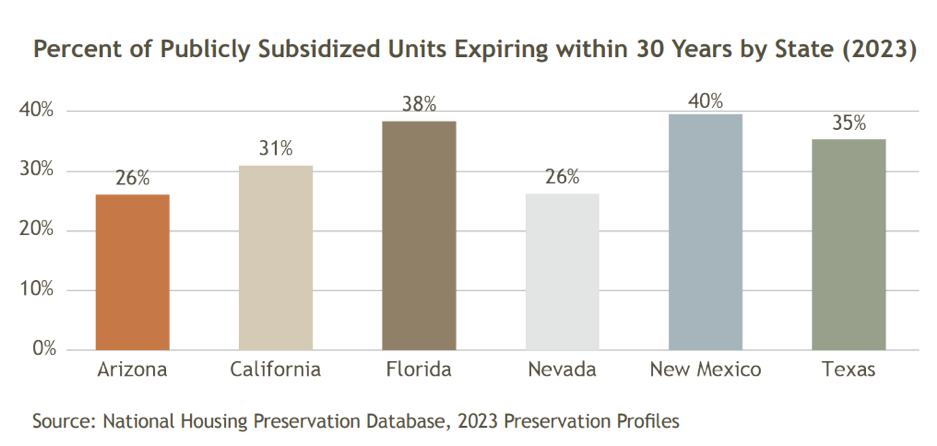

A lack of affordable housing contributes to the problem, Richland said, especially since at least one of the two senior apartment complexes in Prescott subsidized by federal grants has reached the end of the required time to remain low-income rentals. At the other property, where current eligibility status i sunconfirmed, rent increases 10% are raising monthly cost by $100 per month. Cost-of-living increases in senior benefits are only 2% each year.

Richland said she is exploring options for keeping this issue front and center, but that the clock is ticking because eventually many residents won’t be able to afford rents where they’ve lived for years.

“We women don't have any organizations that are supporting us, saying let’s take are of the grandmothers; let’s take care of the mothers,” Richland said. “So that’s where my focus is. In the recent housing assessment, the Pollack study that was presented to the (Prescott) City Council, one of the snippets in there said that single-women’s housing is critical.”

The Housing Needs Assessment report prepared by Elliott D. Pollack and Co. for the City of Prescott, dated May 2025, noted that the average age in Prescott is 60.3.

According to Ashley Cooper, a research analyst for the Morrison Institute for Public Policy at Arizona State University, the group plans to do a specific study in the region on the challenges facing low- and middle-income seniors (anyone over 60) choosing to age in place in their homes or communities. The area was chosen for the focus because of its high cost of living, density of senior population, range of incomes, and mix of urban and rural areas.

The 2024 report found that “top considerations for aging in place include proximity to transportation for those who can no longer drive a car, accessibility features of new and existing homes, and proximity to friends and family for mental well-being.” Since many seniors retired to the area from other parts of the country, families may not be close, so they rely on friends and neighbors.

Richland worries that the continuing demand for housing will leave her and others out in the cold, literally. She lives in the Bradshaw Senior Apartments, which is 17 years into its federal Low-Income Housing tax credit requirement to hold rents steady.

Richland said that many women who are elderly and in poor health are at risj of losing their housing, and teh City should be more proactive about addressing the problem.